Bearing witness through art: Gordon Parks and Carole Boston Weatherford

By Rachel Amaru, Co-Founder

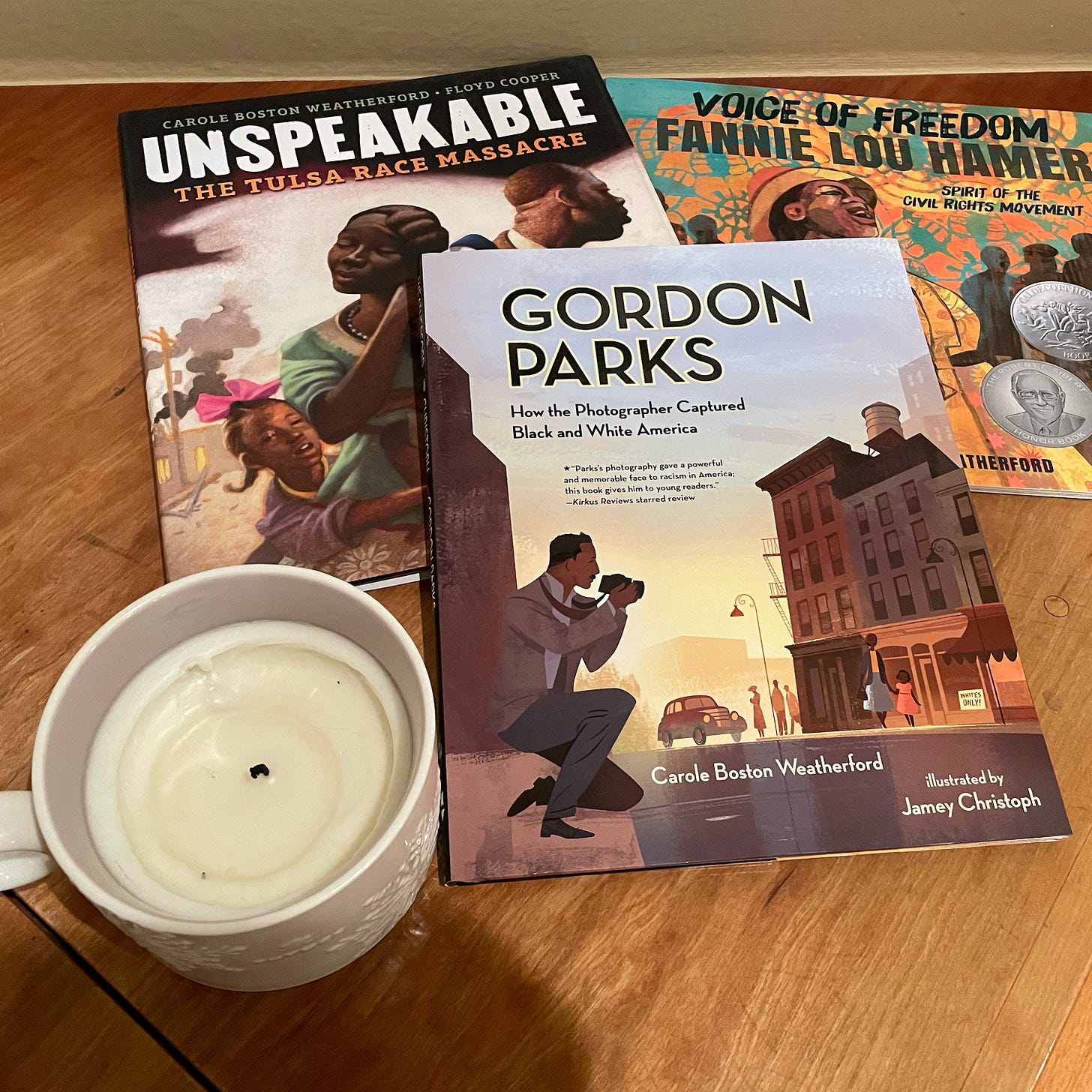

I love Carole Boston Weatherford’s books. I love how she turns history into literature, and vice versa. In addition to Gordon Parks, Good Trouble For Kids has featured Weatherford’s book about the Tulsa race massacre, Unspeakable, and will be featuring Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hamer – Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement. Weatherford also wrote beautiful YA verse biographies of Marilyn Monroe and Billie Holiday, both of which I purchased for my own personal library. Her oeuvre is pretty phenomenal, and covers a wide range of topics. You can read more about Carole Boston Weatherford by visiting her website, which not only details the books she (and her son) have co-written, but also offers biographies, an ongoing blog, and educational resources.

Weatherford’s Gordon Parks: How the Photographer Captured Black and White America is a dramatic introduction to Parks’ life. For those interested in learning more of his biography and seeing more of his art, the Gordon Parks Foundation is a great resource. As Weatherford notes, Parks was truly a Renaissance man. (“He will write novels, make movies, compose music and poetry, and be hailed a renaissance man”).

There is a wonderful short recording of Gordon Parks on Time Magazine’s website of 100 Greatest Photos of All Time (site unfortunately down at the time of this writing). In it, Parks responding to the question of “how do you photograph discrimination.” He relates how he came to make what Weatherford calls his “most famous shot”: his 1942 American Gothic, the extraordinary photo of Ella Watson. As the Gordon Parks Foundation explains, Watson allowed Parks to become an intimate observer of her life, of her friends and family, and he documented their community for four months. By titling his portrait American Gothic, Parks also called attention to Grant Wood’s famous painting and offered his own interpretation of what constitutes both American and gothic.

The National Gallery of Art is another excellent resource to explore Gordon Parks’ photography and the impact of his social justice work. There is an enormous amount of information on their “Uncovering America” project, and I encourage you to explore it more fully. The page on Parks addresses three very significant questions for those of us interested in engaging with the power of art as an act of liberation and resistance:

“How does Gordon Parks use photography to address inequities in the United States?”

“How do Gordon Parks’s images capture the intersections of art, race, class, and politics across the United States?”

“What do photographs in general—and Gordon Parks’s photographs more specifically—tell us about the American Dream?”

I particularly love this quote by Parks, featured on his Foundation’s website:

“I SAW THAT THE CAMERA COULD BE A WEAPON AGAINST POVERTY, AGAINST RACISM, AGAINST ALL SORTS OF SOCIAL WRONGS. I KNEW AT THAT POINT I HAD TO HAVE A CAMERA.”

Parks used art to bear witness to what he saw around him. This act of the artist “bearing witness” is the crux of why I founded Story Remedy, which focuses primarily on the art of story-telling through poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction, and other literary genres. Good Trouble For Kids was founded as a way to address the power of children’s literature to engage with antiracism and social justice, both through story and illustrative art. Weatherford epitomizes an author who recognized that she could use her strengths as a writer for young children, middle school readers, and young adults, to draw attention to current social justice issues, as well as historical ones. It is no surprise that she chose to write about Gordon Parks, whose life was dedicated to bearing witness through film, photography, memoir, novels, poetry, and music (Renaissance man, indeed!) His art continues to tell intense stories.

Because I am certified in poetry therapy, and my passion is sharing poetry and literature, I want to include a poem by Gordon Parks that I find immensely moving. It is not difficult to imagine a black and white photo of this scene.

After many snows I was home again

Time had whittled down to mere hills the great mountains

of my childhood.

Raging rivers I once swam trickled now like gentle streams

and the wide road curving on to China or Kansas City

or perhaps Calcutta

had withered to a crooked path of dust

ending abruptly at the county burial ground.

Only the giant that was my father remained the same.

A hundred strong men strained beneath his coffin

when they bore him to his grave.

Emerging Man, Harlem, New York, 1952 – tribute to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.